BMW K100RS 16V

|

|

| BMW K100RS 16V | |

| Manufacturer | |

|---|---|

| Production | 34 804 units (1983 - 92) |

| Engine | Four stroke, horizontal in line four cylinder, DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder |

| Compression ratio | 11.0:1 |

| Top Speed | 220 km/h / 136 mph |

| Ignition | Bosch Motronic combined ignition/fuel injection system |

| Spark Plug | Bosch XR 5 DC / Beru 12-5 DU / Champion A 85 YC |

| Battery | 20Ah |

| Transmission | 5 Speed |

| Frame | Tubular space frame, engine serving as load bearing component |

| Suspension | Front: 41.7 mm Braced Marzocci fork Rear: Monolever swinging arm |

| Brakes | Front: 2 x ∅285 mm discs, 2 piston calipers Rear: Single ∅285 mm disc, 1 piston caliper |

| Front Tire | 100/90-V18 |

| Rear Tire | 130/90-V17 |

| Wheelbase | 1516 m /59.7 in. |

| Seat Height | 800 mm / 31.50 in. |

| Weight | 263 kg / 579 lbs (wet) |

| Fuel Capacity | 19.7 Liters / 5.2 US gal |

| Manuals | Service Manual |

It could reach a top speed of 220 km/h / 136 mph.

Engine[edit | edit source]

The engine was a Liquid cooled cooled Four stroke, horizontal in line four cylinder, DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder. The engine featured a 11.0:1 compression ratio.

Drive[edit | edit source]

Power was moderated via the Dry, single plate, cable operated.

Chassis[edit | edit source]

It came with a 100/90-V18 front tire and a 130/90-V17 rear tire. Stopping was achieved via 2 x ∅285 mm discs, 2 piston calipers in the front and a Single ∅285 mm disc, 1 piston caliper in the rear. The front suspension was a 41.7 mm Braced Marzocci fork while the rear was equipped with a Monolever swinging arm. The K100RS 16V was fitted with a 19.7 Liters / 5.2 US gal fuel tank. The wheelbase was 1516 m /59.7 in. long.

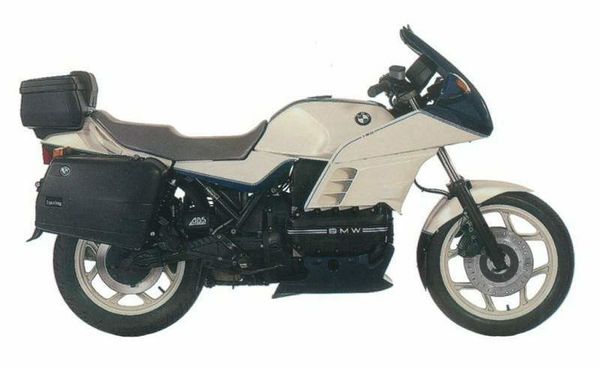

Photos[edit | edit source]

Overview[edit | edit source]

BMW K 100RS 16V

Depending on who you speak with from BMW , its wild and woolly K1 -

introduced in America in the late 1989 - is either the ultimate sportbike or

sport-touring bike. Yet when we recognized the BMW K1 by judging it 1990 Bike of

the Year in Rider's first annual Touring's Top Ten awards, it

wasn't primarily for the machines performance or liberal use of cutting-edge

technology. What pushed the K1 over the top was the chutzpah BMW exhibited by

temporarily setting aside tradition to try something, well, a little

daring. It was high time for the focused German company to exhibit a little

unpredictability, and with the K1 it clearly succeeded. If we had judged the

machine solely on its performance as a sportbike or sport-tourer, the K1

wouldn't have made the cut. Because it doesn't really excel at being either.

The sport-touring aim of the new 1991 16-valve K100RS, however-which is based

primarily on the K1 - is as straight and true as a cannon shot. And that's a

relief to this writer, because in retrospect, 1989s and '90s eight-valve

K100RS-ABS Special possessed a somewhat ambiguous personality, much like the

K1's. While its 82-horsepowcr engine was happiest pulling stumps down low like a

touring machine, the bike had a stiff seat and suspension like a high-revving

sportbike. And though its wheelbase was tourer long, its handlebar was sportbike

narrow. The new 16-valve K100RS had the potential to be similarly confused since

we knew it would be a blend of sporty K1 (see Rider, February

1990) and eight-valve K100RS (see Rider, November 1988)

components. Fortunately, the bike's intent is clear. Although BMW simply bolted

last year's K100RS sport-touring fairing lower cowling and front tender

to the K1 frame, drivetrain and running gear, the addition of some

transition components. such as an all-new dual seat and handlebar as well as

revised footpeg brackets, kept the '91 K100RS from be-coming just another big

sport-touring bike with a He-Man sportbike riding position.

Two or three additional refinements were made to help blend the components of

each bike, but underneath the '91 K1100RS plastic there sits an essentially

unmolested K1. That engine's most evident break with the original K100 design is

its DOHC cylinder head, which uses direct actuation to open its 16 valves. Valve

lash adjustment shims have been eliminated by simply gauging the replaceable

bucket-type tappets, which should prove to be quite long-wearing. The new head

is bolted to the familiar K100 liquid-cooled, 987cc, inline-four cylinder bank.

While the bore and stroke of each cylinder remains unchanged at 67.0 by 70.0mm,

compression is upped to 11:1 from 10.2:1. The engine's new lightened pistons and

connecting rods and a lightened, forged crankshaft also allow the mill to rev

more quickly now, though redline remains at 8,500 rpm. Interestingly, in both

the K1 and '91 K100S 16-valve engines the valve timing is also unchanged from

earlier K100 specification, in spire of a completely new Bosch Motronic combined

ignition/fuel injection system replacing the previous separate L-Jettronic fuel

injection transistorized breakerless ignition (see K1 Tech, Rider,

February 1990). The Motronic system is the same one BMW uses on its cars,

and Ferrari will reportedly use the system to up the awesome Testarossa's

horsepower from 370 to 420.

According to BMW, the changes to the K100 mill are good for an additional 13

horsepower, giving the formerly sluggish four 95 ponies at 7,500 rpm

within shooting range of its Japanese competition. While the 82 horsepower

eight-valve engine still used in the K100IT luxotourer - makes adequate-power

for two-up touring, it is just that adequate. For the sometimes brisk pace and

hard acceleration desired of a contemporary sport-touring machine, more power

was needed, and the 16-valve powerplant delivers.

At a stop, its hard to detect any real difference between the old and new

engines from the rider's seat; the new K100RS starts, idles and sounds just like

the eight-valve K100 RS, which is to say easily and smoothly. Once underway,

however, it becomes swiftlv apparent that the new engine is breathing better,

and in the bottom and mid-range of the zero to 8,500-rpm powerband the revs

still build slowly but with more author-it v. It was easy to motor away from a

stop in third gear with the old K100RS; it's even easier with the new hike. Once

you're speeding past the 5,500-rpm mark the flywheel no longer seems to hold the

engine back and the revs build very quickly. The K100RS's power boost won't make

anything in its class from the Orient turn tail and run, but for sport-touring

most of those bikes arc like driving a thumbtack with a sledgehammer anyway. The

new Beemer on the other hand, makes easily controlled, seamless power from down

low to mid-range just right for Mr. and Mrs. Average, with enough excitement

leftover on top for Walter Mittv.

Despite the power increase BMW opted to use the lower 2.81:1 final-drive

gearing of the earlier K100RS instead of the K1's 2.75:1 ratio, though it

retained the higher top (fifth) gear ratio of the K1. Since their wet weights

are very close and the '91 K100RS wheels and tires are identical to the K1's,

the result is slightly better bottom-end grunt in the lower gears to help get

the fully laden touring bike underway from low speeds or a stop. In spite of all

the engine changes, the 16-Valve in-line four is still pretty buzzy above

4,500 rpm or so, and the new K100RS's lower final drive gearing means that

buzziness begins to reach the rider at a lower road speed than on the K1.

Fortunately for touring riders, that speed is an indicated 76 mph in top gear on

our '91 K100RS rest bike, and below that the bike is reasonably smooth and the

mirrors are clear. Although the beefy K1 frame was otherwise unchanged for use

on the '91 K100RS, BMW went to the trouble of welding on and boring out larger

frame lugs on the ends of the front downtubes in order to accommodate a pair of

rubber spacers. That must mean that with a solid-mounted engine like the K1 s

the '91 K100RS would vibrate intolerably, because now I can't really feel much

difference between the two bikes' levels of vibration.

As with the K1, power is fed to the rear wheel of the '91 K100RS via BMW's

Paralever shaft drive. First seen on its R100GS dual-sport bike, the Paralever

effectively feeds the torque reaction of the shaft drive back into the bike's

frame so that the rear ride height of the new K100RS is unaffected by its

throttle position. I wasn't very impressed with die shifting on our test bike;

the dry clutch has a narrow engagement point almost at the end of the lever

travel, and moving through the gears can be rather notchy at times. What is

gained with the Paralever is often lost with a botched shift.

For a more comfortable ride on the '91 K100RS, BMW has substituted the comparably softly sprung K75S shock absorber for the overly stiff K1 unit. The 41.7mm braced Marzocchi fork is identical to the K1's, though the rebound damping in the fork has been slightly decreased this year for use in both the K1 and new K100RS. The shock has three spring preload stops, but the fork has no external adjustments. Other changes exclusive to the '91 K100RS include a 24-inch wide handlebar, which falls between the mammoth 26-inch unit on the K1 and the old 22-inch K100RS bar. Subsequently, to retain rearward visibility and the envelope of still air the mirrors create for the hands, one-inch spacers were added between the new bike's mirrors and the fairing. A more comfortably padded dual sear with a shape similar to the old K100RS's puts the '91 model's seat height at 31.5 inches, about one-half-inch lower than the old K100RS. Finally, the new K100RS gets all of the K1 instrumentation and its integrated ignition steering lock. BMW claims that the electronic/hydraulic ABS system installed on our test bike-a $ 1,000 option for the '91 K100RS adds about 26 pounds. Our bike was also equipped with the optional saddlebags (S461), which brought the weight of the bike up to 628 pounds fully gassed. That's about 16 pounds more than the K1 with its standard ABS, and 31 pounds heavier than the earlier K100RS-ABS Special. Despite the extra weight, the 16-valve K100RS is vastly superior to its eight-valve predecessor in almost every respect. Though its wheelbase is almost two inches longer, the new K100RS's stiffer chassis, wider handlebar, wider 17-inch front and 18-inch rear wheels and compliant suspension give it much more predictable handling. The bike requires a lot less effort to steer and no longer has to be muscled from comer to corner. It's so much easier, in fact, I was surprised to find the steering damper from the K1 in place on the new K100RS. Kike the K1l, the new K100RS doesn't possess anything remotely like the nimble handling of a 600 sportbike, but it should more than meet the expectations of sport-touring riders unwilling to push an expensive motorcycle beyond prudent limits. We didn't have the opportunity to try the Pirelli and Metzeler Z-rated radials that will also be OEM equipment, but the excellent Z-rated Michelin radial tires lifted to our test bike remain neutral, soak up bumps and stick like flypaper. Up front the Marzocchi fork does an admirable job of steering and suspending the big K-bike, and is near perfectly sprung for sport touring. Most riders will find it more than adequately controlled; for myself I'd like just a touch more rebound clamping. Same with the shock; while the ride is quite comfortable in touring mode with the shock set in the lowest preload position, the back of the bike gets ever so slightly out of shape when you wick it up on twisting roads. Jacking the preload up a notch improves the bike's cornering clearance a little, but doesn't compensate much for the lack of damping. When ridden two-up, the damping situation makes the bike want to stand up in bumpy curves at speed.

Even though the new K100RS's triple disc brakes are straight off the K1, I had much better luck with them on this machine. The four-piston-opposed Brembo calipers in front have smaller leading pistons and pinch floating discs, are quite powerful and linear and give excellent feedback, unlike the spongy feel of our K1 test machine's front brake. Although I didn't use it much the rear brake provides similar performance, and the anti-lock system on our rest machine performed more smoothly than on any BMW motorcycle equipped with ABS we've tried to date.

Between the press intro in Louisiana and an overnight tour on the Left Coast,

I put about 1,200 miles on our test bike, and was very pleased

with its improved comfort level. With its higher, wider bars and

similarly well-placed footpegs, the new K100RS's seating position is still

sporty but much better suited to long rides than the old bike. BMW didn't give

in entirely the seat is still pretty hard but again, much more comfortable,

almost enough for an entire tankful. And the K100RS fairing has always been one

of my favorites, offering ample hand, chest and leg protection. Its adjustable

wing on top of the windscreen doesn't offer much change in the height of the air

flow over it, but it does allow you to tune out a whistle in your helmet face

shield, or direct the strongest flow to the center of your shield to clear off

water droplets.

On the road the '91 K100RS returned great gas mileage; the lowest I could get

it to go was 49.4 over a tankful consumed by what the average rider would

consider pretty spirited riding. My high of 52.2 gave the big Beemer a range of

over 250 miles from its 5.2-gallon tank. By then I was pretty tired of

staring at the warning light, however, which comes on at the 1.3-gallon mark.

There-is no reserve petcock.

The new latch design on the optional saddlebags allows a single key to be

used for all of the bikes locks; now the latches are easy to unlock and

difficult to open instead of vice versa. In addition, though still plenty roomy,

the bags wont hold most contemporary full-face helmets other than BMWs, and

block the bike's helmet lock when installed.

Still, in daily use the revamped K100RS is much more pleasant to live with

than its forerunner. Although the storage box under the seat directly

above the battery had to be sacrificed to make way for the Motronic

computer, if you opt for it the ABS computer also mounts in the batten area,

treeing up the entire tail-section compartment. Even after stowing BMW's

excellent tool and flat repair kits within, there's still some space

leftover. Of course, now it's a lot tougher to get to the battery to hook up an

electric vest or whatever, so BMW has located its remote accessory socket in a

convenient spot just under the tank. The slick flip-out centerstand handle

returns on the new K100RS, and though the sidestand is free from any of BMWs

former automatic retraction devices, now it kills the ignition when deployed.

That means you can't warm the bike when it's parked on the sidestand, but you

can kill the engine by deploying it. lit for tat.

And such is life with a BMW. Not only will you pay a lot more money up front

than you might be used to the '91 K100RS starts at $11,590 without ABS or

saddlebags if you're accustomed to the nearly universal way in which all

Japanese motorcycles do things, at first living with a Beemer can be mildly

frustrating. With the K100RS, however, BMW has finally set aside some its most

annoying traditionssuch as the lack of a compliant suspension, comfortable seat

or integrated ignition steering lock for almost Japanese!ike performance in

many important areas. Combine this with a high resale value and certain other

stead fast traditions that are simply the BMW way, and the 1991 K100RS remains a

unique but very competent sport tourer among an abundance of sameness.

Source Rider Magazine 1991

| Make Model | BMW K100 RS 16V and SE model |

|---|---|

| Year | 1989 - 92 |

| Production | 34 804 units (1983 - 92) |

| Engine Type | Four stroke, horizontal in line four cylinder, DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder |

| Displacement | 987 cc / 60.2 cub. in |

| Bore X Stroke | 67 x 70 mm |

| Compression | 11.0:1 |

| Cooling System | Liquid cooled |

| Lubrication | Wet sump |

| Engine Oil | 10W40 |

| Exhaust | Stainless steel, 4 into 1 |

| Induction | Bosch Motronic combined ignition/fuel injection system |

| Ignition | Bosch Motronic combined ignition/fuel injection system |

| Spark Plug | Bosch XR 5 DC / Beru 12-5 DU / Champion A 85 YC |

| Battery | 20Ah |

| Starting | Electric |

| Max Power | 70 kW / 95 hp @ 7500 rpm |

| Max Power Rear Wheel | 61.7 kW / 83.9 hp @ 8250 |

| Max Torque | 86 Nm / 8.8 kgf-m / 63 ft-lb @ 6000 rpm |

| Clutch | Dry, single plate, cable operated |

| Transmission | 5 Speed |

| Final Drive | Shaft, gearing 2.81:1 |

| Gear Ratio | 1st 4.50 / 2nd 2.96 / 3rd 2.30 / 4th 1.88 / 5th 1.61:1 |

| Frame | Tubular space frame, engine serving as load bearing component |

| Front Suspension | 41.7 mm Braced Marzocci fork |

| Front Wheel Travel | 185 mm / 7.3 in |

| Rear Suspension | Monolever swinging arm |

| Rear Wheel Travel | 110 mm / 4.3 in. |

| Front Brakes | 2 x ∅285 mm discs, 2 piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | Single ∅285 mm disc, 1 piston caliper |

| Wheels | Alloy, 8 spoke |

| Front Rim | 2.75 x 17 Z |

| Rear Rim | ZMT H 2 |

| Front Tire | 100/90-V18 |

| Rear Tire | 130/90-V17 |

| Dimensions | Length 2220 mm / 87.4 in Width 800 mm / 31.5 in Height 1271 mm / 50.0 in |

| Wheelbase | 1516 m /59.7 in. |

| Ground Clearance | 175 mm / 6.9 in. |

| Seat Height | 800 mm / 31.50 in. |

| Wet Weight | 263 kg / 579 lbs |

| Fuel Capacity | 19.7 Liters / 5.2 US gal |

| Reserve | 4.9 Liters / 1.3 US gal |

| Average Consumption | 4.7 L/100 km / 21.3 km/L / 50 US mpg |

| Braking 100 Km/h / 62 Mph - 0 | 38.7 m / 127 ft |

| Standing ¼ Mile | 12.5 sec / 172 km/h / 107 mph |

| Standing 0 - 100 Km/h / 62 Mph | 4.3 sec |

| Top Speed | 220 km/h / 136 mph |

| Colours | White, Red, Blue |

| Manual | Epll.no-ip.com |

| Source | Rider Magazine, 1991 |