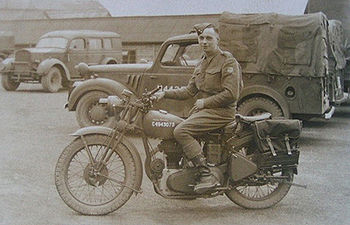

Royal Enfield WD

The first dispatch riders[edit | edit source]

Its dark and bitterly cold, the rain has stopped and the winding road ahead is lit only by the dim slit of light from the headlamp of the motorcycle.

There is a rhythm to the engine that is reassuring and a crack and bark like gunfire to the exhaust silencer that penetrates deep and further than the orange glow of its beacon light guiding the way. As we climb the gradient on the wet and slippery road I keep my eyes alert for sabotage on the highway ahead. As we crest bumps in the road the panniers rattle their precious cargo of government documents. Those secret codes, an officer’s orders, or maybe welcome good news from a theatre of war. Just one half hour and I’ll be at my destination, just thirty minutes. The moonlight is quite bright this night so I can just pick out the silhouette of the town ahead plunged in darkness. Tall towers of factory chimneys claw at the heavens and herald the transition of town and country, the new and the old. I smell pine mixed with dank earth as my damp misted goggles press uncomfortably around my eyes and I taste the musky cloth scarf over the lower part of my face. The motor stutters and falters momentarily. Instinctively I reach down to the reserve tap with my left rain-soaked leather gauntlet, and peace and contentment is restored by the two pints of petrol that are fed to the carburetor for the last fifteen miles of this night time journey.

A piping hot mug of tea and a warming renewing meal await me at my destination and it is its eager anticipation that carries me through this loneliness of the long distance Second World War dispatch rider.

Sound familiar? Long before the first urban motorcycle dispatch riders in the 1970’s there existed like-minded souls that rode Jurassic motorcycles some extraordinary distances around the clock in all weathers. There was no such thing as Cordura or heated grips, Scottoilers, or shaft drive transmission fitted to their mounts. Modern day dispatch riders complain of poor road surfaces, but the wartime DR had to negotiate bomb damaged inner city roads on machinery that had a rigid rear end and Girder forks – and lighting was near non-existent both on and off bike.

Never mind a postal code being spelt wrongly on a package or a Richard Head of an address, these riders had to get around the country on roads where signposts had sometimes been removed to help confuse a potential approaching invading army! Next time you’re soaked through, looking for an obscure address in the middle of nowhere, and the Divvy is firing on three cylinders, remember, it could be much worse.

To get some slight fraction of an idea of what it must have been like to have been a motorcycle dispatch rider in the 1940’s, I test rode a genuine 1943 Royal Enfield WD/CO army dispatch motorcycle for a few days.

Sixty-four years ago, a new Royal Enfield motorcycle is delivered just like many others to join the war effort in the bitter fight against a darker side of humanity that changes its name, but seemingly will always return.

There was a passion that only the very best was good enough for our troops engaged in this desperate struggle and so manufacturers incorporated improvements from time to time. Royal Enfield replaced its gutless side valve 350 with a new overhead valve design and thus the WDCO was brought into military service. This actual WDCO, the subject of this test and review, was just one of the many motorcycles that were delivered to our forces. Indeed some thirty thousand were supplied to the army and three thousand to the air force. Perhaps the best known war motorcycle was the BSA M20, but there were others too, manufactured by Matchless, Norton and Ariel. Furthermore, a wide range of civilian motorcycles were requisitioned to help in the war effort and although a very few owners hid their machines to avoid losing them, many understood that putting them into military service was the right thing to do to.

If you look at the WDCO in profile you can see the DNA that has followed through to the Indian Enfield that incredibly is still produced today. The rear toolboxes, the primary side with its double-ended oil pump and the attached cast-in oil tank, all add to the cut of its jib and define it as a fine Royal Enfield motorcycle. The engine is conventional, featuring overhead valves in a cast iron head with a very low (approximately five to one) compression ratio to handle the low-grade pool petrol of the time. A little unconventional in the motorcycle industry was the floating bush big end made of brass and coated with white metal, a feature that has survived and can be found in modern Indian-made Royal Enfield Bullets today. The bicycle is conventional with a rigid rear and girder fork and is equipped with no less than three toolboxes. The individual contract number was displayed in white on the petrol tank and is a calculation of the frame number and supply contract number. Three stands are fitted: one at the rear; an off road spiked side stand; and another that forms part of the mudguard stays on the front wheel. The rear wheel is a quickly detachable design, which incorporates a split spindle; remove this and three nuts and the rear wheel simply drops out. To facilitate this the rear portion of the mudguard, the carrier, pannier bags and pillion seat can be removed by slackening four nuts. The split spindle also permits an inner tube to be replaced without removing the rear wheel. The WDCO had a reputation of being a very robust and reliable military dispatch riders’ motorcycle indeed.

After the war, the Army returned a large number of WDCO motorcycles to the factory. These were refurbished and sold to the British home market because the ‘new’ models were exported to earn foreign currency. This refurbishment meant that sometimes frames from one bike were mixed with engines and parts of another. The result was an ‘as good as new’ reliable motorcycle. Advertisements for reconditioned WDCO motorcycles appeared from 1946 to as late as the mid 1950’s! Fred Fearnley LTD offered “practically unused and equal to new” WDCO’s finished in immaculate maroon and chrome or black and chrome at just ninety-five pounds five shillings.

The motorcycle in this test, which was the subject of a careful restoration over twenty years ago by the then military motorcycle expert of the Royal Enfield owners club, has matching numbers and its original registration number from when it was demobbed in 1946. It also retains all of its period features and is a very correct example that appears to have never been civilianised.

Out on the road, the motorcycle is willing and the gearshift from the four-speed Albion gearbox is slick and sure. Yes really, it surprised me too! There is a huge jump in the gearing between third and fourth, which suits the WDCO as fourth gear becomes an on road overdrive, while first, second and third are ideal for unpaved or more straining work. This motor wouldn’t understand what vibration was with its very low compression, so in top gear at 45mph and above the engine is creamy and smooth. Top speed is around 65mph but 50mph seems an ideal cruising speed, and crucially it can travel as low as 12mph in top gear for convoy work. The clutch is very light which makes for a very pleasant riding experience. The Smiths unlit speedometer records just seven hundred and ninety seven miles in the twenty years since its refurbishment.

The matt black silencer emits a very pleasant bark that adds to the real motorcycle experience immensely. The front brake works well, but the rear brake is simply too aggressive; it has far too much leverage on the pedal, especially for squadies boots.

There is a lot of bow locks, fuss and bother spoken about the handling and comfort of girder forks and rigid rear equipped motorcycles. This WDCO has very compliant girder forks that respond well to the road surface and you can easily tune the damping by using the hand-operated dampers on each side of the girders. By turning them towards the rider (the right hand one has a left hand thread) it dials in the required amount of damping. Also, unlike telescopic forks, girders don’t suffer from stiction under load and can handle immense sideways forces. It’s an intriguing and very pleasant sight watching the girder fork in action over an irregular surface with springs flexing and adjusting with no anticipated ‘far canal’ drama. The rigid rear works well too and holds the road well with the sprung solo saddle doing its work in isolating the rider from most of the road’s worst surface disturbances. I am able to bank the motorcycle very easily at footrest scrapping angles with no problems and the line stays true with but the lightest touch to the handlebars.

One thing that surprises the modern rider is the very low ground clearance considering its purpose, and the possibility of extensive use on unpaved roads. At the time “Motor Cycling” mildly criticised WDCO’s abilities off road citing the ground clearance as less than adequate. Checked with a tape measure, the ground clearance is very similar to the BSA M20, whilst the low point extends for just sixteen inches compared to a massive 20 inches on the BSA. Extended low clearance is one of the limiting factors when tackling off road humps, and as there is no skid plate fitted to the underside of the frame rails, they can hook up the bike and topple the rider. In a 1942 road test review the “Motor Cycling “ writer criticises the motorcycle’s road holding abilities on right hand bends on freshly sand covered tarmac! Hmm… and why just right hand bends? I wonder how it would cope on today’s diesel-covered city routes?

I thought that the period writer’s comments should be tested and so to check out the motorcycle’s handling I took it off road on some green lanes and scrambling tracks that I have ridden before on a variety of different machines. The first thing you notice is just how low the weight is, making it very simple to manage across the rough stuff. It feels like a vintage trials motorcycle with its low slogging torque and impressive turning circle. Even with road tires fitted the WDCO tackles muddy tracks and woodland paths with the ability and aplomb of a stag.

Whilst it is limited by its ground clearance compared to say a modern scrambler, I was surprised and impressed by how much ability it actually had in road-equipped trim. Also surprising was the way the it handled a fast pace across fields with the girder fork working very well indeed. Between sections of green lane and byways I rode briskly along mud-covered tarmac lanes and the ride was as sure footed as a mountain goat. I can personally vouch for the integrity of this WDCO across a number of different surfaces and gradients. Out on the open road it enjoys cruising in top gear where its sound of a well-oiled machine provided a wonderful accompaniment to a glorious winter's day. In town it can do the urban thing nicely, it’s a cool ride, people stop to take a look and it seems to draw a crowd, even from the blade and gixer brigade at bike meets.

Its simplicity, authenticity, and integrity are attractive features in an age where sadly vacuous government spin is too often the order of the day. This Royal Enfield WDCO, once a war baby and now a veteran, is still soldiering on as tough as nails and with an open heart as British and resilient as our own Tommy Atkins.