Suzuki GS425E

|

|

| Suzuki GS425E | |

| Manufacturer | |

|---|---|

| Production | 1979 |

| Class | Standard |

| Engine | Four stroke, parallel twin cylinder, DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder. |

| Compression ratio | 9.1:1 |

| Transmission | 6 Speed |

| Suspension | Front: Telescopic fork Rear: Twin shocks, coil spring over |

| Brakes | Front: Single disc, 11in Rear: Drum, 7 in |

| Front Tire | 3.00-18 |

| Rear Tire | 3.75-18 |

| Seat Height | 787 mm / 31 in |

| Weight | 173 kg / 382 lbs (dry), |

| Recommended Oil | Suzuki ECSTAR 10w40 |

| Fuel Capacity | 15 Liters / 4.0 US gal / 3.3 Imp gal |

| Manuals | Service Manual |

Engine[edit | edit source]

The engine was a Air cooled cooled Four stroke, parallel twin cylinder, DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder.. The engine featured a 9.1:1 compression ratio.

Drive[edit | edit source]

Power was moderated via the Wet multiplafe.

Chassis[edit | edit source]

It came with a 3.00-18 front tire and a 3.75-18 rear tire. Stopping was achieved via Single disc, 11in in the front and a Drum, 7 in in the rear. The front suspension was a Telescopic fork while the rear was equipped with a Twin shocks, coil spring over. The GS425E was fitted with a 15 Liters / 4.0 US gal / 3.3 Imp gal fuel tank. The bike weighed just 173 kg / 382 lbs.

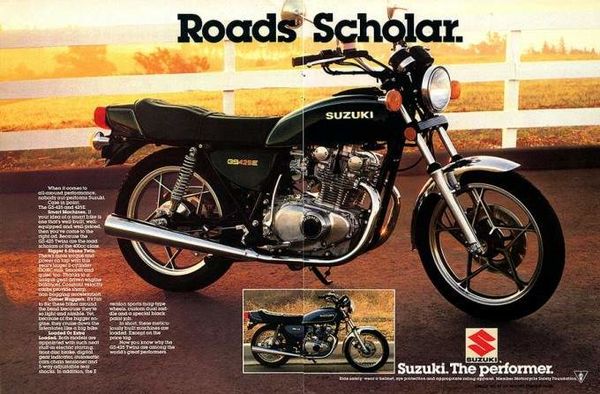

Photos[edit | edit source]

Overview[edit | edit source]

Suzuki GS 425E

TWENTY-THREE. THERE'S A NUMBER

TO conjure with. You may think there's absolutely nothing about the number

23 to commend it or make it special. Well, you'd be wrong, there's plenty.

For a start, well . . . errr, lemme see. Oh yeah, John Keats was 23 years

old when he wrote 'Ode on Melancholy', and that was no mean achievement. If

you add 2 and 3 together you reach five, and your writer was five years old

when he first mastered infinitesimal calculus. Ahem.

Oh yes, and one other thing.

Twenty-three is the amount of cc by which Suzuki have increased the volume

of their GS400. Not only have they added 23cc, but they've renamed the bike

the GS425. If that isn't a masterpiece of absurdity I'll ride GSs from now

until Christmas. Hogging-out the 400 by 23cc has rekindled my faith in Japanese

inscrutability. Eastern designers were becoming boringly logical in a

Western kind of way.

Gone are the days of the

arbitrary displacement figure, such as the 360 and the 900 (although the

latter has returned in a blaze of glory with the new Honda). Suzuki have

taken the Blue Riband for meaningless the 423cc motorcycle, called the

425.

But why? Surely nobody who gave the original a miss is going to be attracted

by this addition, unless of course the styling change is all they're

interested in. Actually you couldn't blame them for that, it's a very slick

looking bike. Ours was black with contrasting gold decals on tank and side

panels, but couldn't they run to a bit of paintwork instead of tapes for the

striping?

Basically the motor is the same

DOHC balance-shafted unit as the GS400. Red-lined at nine grand it

appreciates being treated like a 2-stroke, ie held wide open and whanged

through the gears. No, that's not what I mean, perhaps a better way of

putting it is to say that the characteristics are such that it encourages

you to treat it that way.

There's a definite power band at

the 4000rpm mark and I kept running out of cogs a lot quicker than I

expected. The gearing wasn't altered along with the hop-up and the result

is that it accelerates quicker than the 400 (which was no sluggard anyway)

and turned in a respectable 14.75sec standing quarter. That's more than half

a second faster.

A flick back to Peter Watson's

test of the 400 in May of last year also shows that with a few thousand

miles under its belt, this motor loosens up considerably, to the tune of

10mph on the top speed. So maybe our 101.8mph top whack could be improved on

later this year when the test bike has had a bit more of a thrashing.

When I got on the bike for the

first time I could hardly believe that it really was a 425, it felt so small

and low, and this was enhanced by the riding position. The bars are

practically flat and at 27ins wide they're narrow too, but I felt the

footpegs could have been moved back three or four inches to increase

rider-lean and reduce the feeling of being perched on top of and a third of

the way back on the machine.

This position did tend to make

me feel a bit exposed on high speed bashes but I can't complain about the

comfort, it's a nicely

padded seat and there were no aches or pains apparent after a motorway

thrash. Incidentally, Timmy, that long-legged denizen of the Bike office,

complained that the most comfortable riding position for him on this bike

meant that his knees rubbed on the Suzuki decal and they did get chappie

chapped.

The handling hasn't changed with the motor, it is still very rigid and

totally predictable. During most of the test period the country was under a

few inches of white stuff which made assessment of the handling a little

difficult.

However, crossing London in good

weather in the rush hour was fun, the general narrowness of the bike and its

zoom-ability made it a great traffic dodger. Funnily enough, although the

front end felt heavy (it dived like a U-boat under braking) it was from this

department that I got the only negative vibes in the handling department. On

long high speed corners there was the tiniest hint of front wheel flutter

but I'd be inclined to put that down to the Jap Dunlops fitted as standard.

Here's one of those weird contrasts I was talking about: Suzuki build

themselves a great little frame based on the GS750, put on some of the

nicest mag wheels you're ever likely to come across and then spoil it all

with rubbish tires. They are inscrutable, these orientals. Or are they just

cheapskates?

A

single 11 in disc up ront and a seven inch drum behind provide the stopping

power, and very effective they both are too, despite the way the forks dive.

Of course, any rain reduces the disc to the efficiency of a piece of soggy

cardboard.

Mechanically it's a very smooth and qujet engine, at high speeds you get a

slight tingle through the bars but nothing to write home about. The balance

shafts and 180 degree crank do their jobs very well. Noise is kept to a

minimum because there are only two chains on the whole bike, one to the back

wheel and another driving the cams.

There's a nifty little automatic

camchain adjuster too, a spring driven gizmo that hangs out under the carbs

on the right hand side of the bike. While we're in the area of the two 34mm

Mikunis another contrast rears its head. When will the Japs give us carb

fitments capable of a little English weather? Corrosion was very bad on the

hose clamps, choke lever, throttle return spring and all the other linkages.

Would it cost too much to have them plated before leaving the factory?

And so to the choke and general

starting of the bike. Not too hot I'm afraid. In the handbook it tells you

to switch on the choke, press the starter (there's a kickstart too) and

then, using the choke lever, regulate the revs to 2,000 for 30 sec in

summer, longer in winter, before moving off. Well, that's all fine and dandy

but I never could get the revs above 1,000 on the choke anyway and during

the very cold weather it took a long time for the engine to warm up. It

didn't help to leave the bike ticking over on choke for a while before

getting on, because after a while the revs would falter and die. As soon as

you open the throttle it by-passes the choke anyway so if you forget about

it you find yourself arriving at the first set of traffic lights, closing

the throttle and then wondering why the engine stopped.

That's just a niggle though.

Two more annoying points were a steering lock that was jammed (in the off

position thank God) and the fact that you still have to dismantle the

left-hand exhaust to get the back wheel out. Jeezus, I thought that went out

with 750 Commandos.

The instrument console is pretty impressive, and just plain pretty, too. Across the top is a clear and helpful digital gear indicator, underneath that a main beam light, indicator light and neutral light. The dials keep their seductive rosy glow at night. Sensibly, Suzuki have re-calibrated their speedo to show the all-important 30 and 70mph marks but the instrument error was pretty bad, giving 27.08mph at an indicated 30mph and 54.30 at an indicated 60. Lighting is adequate but nothing special, and dip beam failed after a time. The other switches and electrics keep up the famous Suzuki standard, however. One complaint in the handlebar area was the mirrors, they're a strange design. There's a post that screws onto the switch console with a branch into which the mirror stem screws. The mirrors swivel at the top. Despite three adjustment points I found it hard to get a good rearward view without a good dose of elbows showing.

Source Bike 1979

| Make Model | Suzuki GS 425E |

|---|---|

| Year | 1979 |

| Engine Type | Four stroke, parallel twin cylinder, DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder. |

| Displacement | 423 cc / 25.8 cu in |

| Bore X Stroke | 67 x 60 mm |

| Compression | 9.1:1 |

| Cooling System | Air cooled |

| Induction | 2 x 34 mm Mikuni carburetors |

| Starting | Electric and kick |

| Clutch | Wet multiplafe |

| Max Power | 29.8 kW / 40 hp @ 7000 rpm |

| Transmission | 6 Speed |

| Final Drive | Chain |

| Front Suspension | Telescopic fork |

| Rear Suspension | Twin shocks, coil spring over |

| Front Brakes | Single disc, 11in |

| Rear Brakes | Drum, 7 in |

| Front Tire | 3.00-18 |

| Rear Tire | 3.75-18 |

| Seat Height | 787 mm / 31 in |

| Dry Weight | 173 kg / 382 lbs |

| Fuel Capacity | 15 Liters / 4.0 US gal / 3.3 Imp gal |